This blog explores two key systemic issues present in both the Post Office Horizon Scandal and the Grenfell Tower fire. It considers the role of knowledge and power in silencing voices; and how and why the consequences of tragedies and miscarriages of justice are so unfairly borne.

Table of Contents

- Table of Contents

- Background

- The Post Office Horizon Scandal

- Two Systemic Issues – Grenfell & the Post Office Scandal

- Summary and Conclusions

- About Me

Background

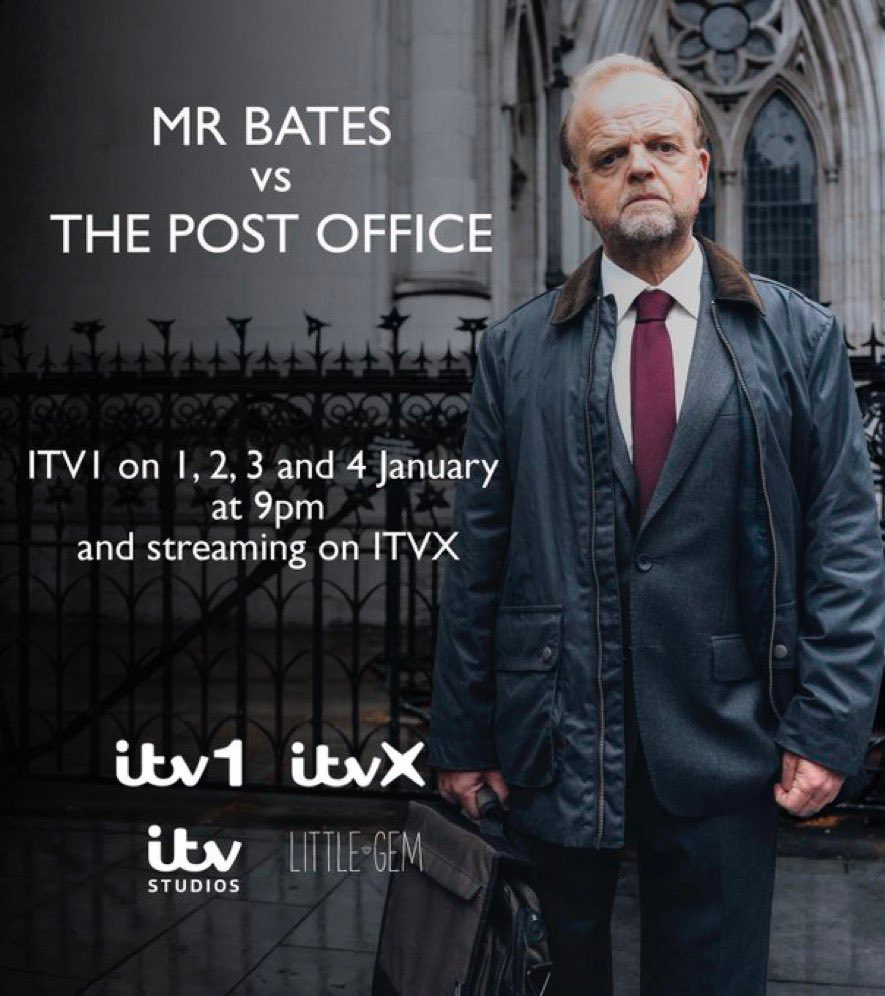

Many are expressing shock and outraged at the Post Office Scandal, following ITV’s ‘Mr Bates v The Post Office’. The series dramatises the Post Office Scandal. Hundreds of subpostmasters were wrongly prosecuted over a 15-year period for shortfalls in their accounts. The shortfalls were a result of a bugs in an IT system, Horizon. Many lost their savings, jobs and community standing. Some were jailed and four suicides have been directly linked to the Scandal.

They say you shouldn’t make a drama out of a tragedy. Thank God that in this case they have. The four-part ITV series on the Post Office Horizon scandal is a taut, coruscating indictment of official complacency, deceit and wilful obstructionism that has enraged many of the 3.6 million viewers and made an overwhelming case for an immediate settlement of the wrongs caused by what has become the greatest miscarriage of justice in England in modern times.

The Times view on the Post Office: An Endless Scandal 5 January, 2023

But, there are some communities who won’t be shocked. Because the Post Office Scandal reflects the same systemic issues they have experienced. From Hillsborough, to the Contaminated Blood Scandal, to the Grenfell Tower Fire and the Building Safety Crisis or Cladding Scandal. There are similarities accross these that point to the depth of unethical and immoral acts by government and industry alike. And highlight a reality of how we respond to disasters and miscarriages of justice. A response that is harsh and unforgiving and plays out in devestaing consequences for ordinary people.

From 2011 to 2014, I lived on the 21st floor of Grenfell. On the 14th of June 2017 I watched it burn. Seven of my immediate neighbours died. My book ‘Catastrophe and Systemic Change’ articulates how the issues we see in disasters are systemic versus disaster specific.

I said to someone the other day that Grenfell opened my eyes, to a world I now cannot ‘unsee’. That beforehand, I was naive, and believed in the goodness of the state and those in positions of power. And now, all I see is the the depth of the systemic issues that play out with such devestating consequences.

It is this lens that I bring to looking at the Post Office Scandal. There are two systemic issues that are worth highlighting:

- How Power and Knowledge end up silencing voices and

- How and why the consequences of these events are so unfairly borne.

But first some background on the Post Office Horizon Scandal.

The Post Office Horizon Scandal

In 1999, the Post Office began automating accounting processes at about 14,000 Post Office branches. This saw the introduction of a centralised computer system called Horizon. Horizon was originally developed by ICL which was acquired by Fujitsu in 1998. This system replaced traditional paper-based accounting practices.

Unexplained Shortfalls

A number of subpostmasters suffered unexplained accounting shortfalls once the system was introduced. The contracts they had with the Post Office were not changed with the move to digital accounting system. This meant the subpostmasters were liable for any accounting losses.

The Horizon system provided very little paper trail to cross check accounts, and many were therefore unable to prove they were not at fault. Additionally, when investigated or prosecuted they were not allowed access to their records or computers. They were effectively locked out of their premises.

Uncompromising defense of the Horizon system

When subpostmasters said that the discrepency might be due to the new system, they were told that they were the only one experiencing an issue. The Post Office used its legal teams and resources to defend itself against accusations in court. Justifying these actions by saying it was stopping subpostmasters from ‘jumping on the Horizon bashing bandwagon’.

According to computer weekly, the Post Office lied to journalists, politicians and anybody else who questioned the robustness of the Horizon system. In some cases, when submpostmasters responded to prosecutions by bringing in an IT expert, the Post Office settled cases.

Hundreds were made bankrupt. Losing their livelihoods and savings as they were forced to pay the Post Office to cover shortfalls that didn’t exist outside the Horizon system. Some took plea bargains, admitting guilt even though they were not at fault.

The lives of the victims and their families were severely impacted. Several suicides have been linked to the scandal as well as many cases of illness caused by stress.

Prosecutions and Prison Sentences

The UK Government is the sole shareholder of the Post Office. The Post Office has private investigation and prosecution powers with no need for police involvement.

The Post Office, between 1999 and 2105, wongly prosecuted 735 subpostmasters for crimes such as theft and false accounting because of of technical faults with the Horizon IT system.

Hundreds of subpostmasters were sent to prison. Many more received punishments such as being forced to do community service and having to wear electronic tags. They lived their lives with criminal records and many experienced being ostracised by their communities.

Mr Bates – we’re not alone

In 1998, Alan Bates together with his partner Suzanne Sercombe bought a Post Office in north Wales. The manual accounting system was replaced by the Horizon system in 2000. Bates then experienced unexplained losses and refused to sign off his accounts as he was sure the discrepencies were down to computer error.

The Post Office tried to force him to sign off his accounts but he refused. The Post Office then terminated his contract, taking his job, life savings and retirement plan with it.

Bates sent up a website to find other subpostmasters having troubles and campaigned at events.

In 2009, he was one of seven cases highlighted in a Computer Weekly article. This article proved a turning point as the subpostmasters realised they were not alone.

A few months after the Computer Weekly article, Bates had been approached by more subpostmasters who had experienced similar problems. They formed the Justice for Subpostmasters Alliance (JFSA) and began meeting in Fenny Compton, a village in Warwickshire. People who had been impacted from accross the country showed up to these meetings and a campaign was born.

The (Long and Continuing) Road to Justice

Members of Parliament began to raise concerns. Notably James Arbuthnot (now in the House of Lords) whose constituent subpostmaster Jo Hamilton was caught up in the scandal) In response to these concerns, in 2012, the Post Office set up an investigation and mediation scheme to investigate and resolve issues.

As part of this scheme, the Post Office appointed and paid Second Sight a forensic accountancy company to investigate cases. In 2013, Second Sight produced an interim report that revealed serious concerns about the Horizon system.

In March 2015, on the eve of the publication of the final investigation report, Second Sight’s work was stopped and the mediation scheme was closed. This final report found there was a real possibility that there had been miscarriages of justice in the Post Office prosecutions. It said the organisation had been too quick to prosecute before investigating evidence.

Following this, the Justice for Subpostmasters alliance began their own civil proceedings and began a group litigation. Eventually in 2019, the Post Office agreed to settle with 555 claimaints. Accepting it had previously “got things wrong in [its] dealings with a number of postmasters”. It agreed to pay £58m in damages. The claimants recevied a share of £12m after legal fees were paid.

A few days later, a High Court judgement said that the for the first 10 years of its use, the Horizon system was not “remotely robust”, and still had problems after that. According to the judge, the system contained “bugs, errors and defects“. And there was a “material risk” that shortfalls in branch accounts were caused by the system.

The judge ruled that the prosecutions were wrongful, and that they were an affront to justice. This opened the door for victims to appeal their convictions.

To date (January 2024) 93 convictions have been overturned and many more are expected.

A statutory public inquiry is currently in session and evidence has included hearing the devestating human impact of the scandal.

The Inquiry was established in non-statutory form on 29th September 2020. It was converted to a statutory inquiry on 1st June 2021.

The Post Office Horizon IT Inquiry (“the Inquiry”) is led by retired high court judge Sir Wyn Williams who has over 28 years’ judicial experience. Sir Wyn is tasked with ensuring there is a public summary of the failings which occurred with the Horizon IT system at the Post Office leading to the suspension, termination of subpostmasters’ contracts, prosecution and conviction of subpostmasters.

The Post Office IT Horizon Inquiry

Compensation

While much progress has been made toward justice, in the four years since the High Court Judgement, most submasters have yet to receive the compensation they are due.

According to Computer Weekly:

The Post Office has a number of different compensation schemes but progress to pay subpostmasters, many of whom are in financial difficulty, is too slow. Many have died before receiving the money they are owed.

Computer Weekly

Two Systemic Issues – Grenfell & the Post Office Scandal

I’ll now explore the two systemic issues: Power, knowledge and the silencing of voices and how and why consequences are unfairly borne. I’ll consider how these issues played out in the Post Office Scandal and Grenfell (and reference some other examples).

For those that do not know what happened at Grenfell, a good introduction is this tweet by journalist Pete Apps. Written on the fifth anniversary of the fire, it points to the multiple failures that contributed to 72 people dying in their homes. The depth of wrong-doing deserves the same level of outrage as the Post Office Scandal.

As an aside, a further similarity between Grenfell and the Post Office Scandal is the role of journalists. In the case of Grenfell, Pete and in the case of the Post Office, Nick Wallis. Both have written books which I would highly recommend.

They demonstrate the best of journalists’ role in holding the state to account.

Power, Knowledge and Silencing Voices: The Dark Side of Expertise

Key issues

Whilst the benefits of deep domain or expert knowledge are unquestionable, there is a dark side to expertise. There are two main ways this is evidenced in the Post Office Scandal and Grenfell:

- Misplaced trust in expertise. Expertise can (intentionally or not) lead to misplaced trust and a failure to question or demand information from experts. General practitioner and serial killer Harold Shipman is an extreme example of misplaced trust. Shipman targeted elderly patients who trusted him as their doctor. Killing them either by a fatal dose of drugs or prescribing abnormal amounts. He is thought to have killed in the region of 250 patients.

- The dismissal by those in power of other non-expert ways of knowing (e.g., Tacit Knowledge). In every major disaster I’ve studied somebody has raised a concern. If it had been listened and responded to it could have prevented the disaster. In most of these cases, power and knowledge play a critical role in this silencing of voices. Typcially it is those with less power such as front line workers or non-experts’ views such as residents or the public that are not heard or taken seriously.

- For example, on Saturday 5 October 1999, 31 people were killed in the Ladbroke Grove rail crash. Michael Hodder, the train driver, who died in the crash, passed a red signal and collided with another train. The subsequent Inquiry revealed that since 1993, train crews had warned about the “inadequate sighting of certain signals,” including SN109, the one missed by Mr Hodder. In the preceding six years, seven train drivers had failed to see the red light and stop. No action had been taken.

- And consider how the views of nurses are often dismissed by doctors. Or how patients and their families are not always given all the information about their conditions. Or how female of more junior aircraft pilots don’t speak up or are ignored.

Both of these issues: misplaced trust and dismissal of tacit or ‘non-expert’ knowledge often co-exist.

As in the case of Martha Mill’s preventable death. Martha suffered an accident leading to pancreatic trauma. While in hospital she developed sepsis and was not given the care she needed, and died.

Following her death, her parents have campainged for Matha’s law which would give patients the right to ask for a second opinion. In 2023 the minister for health said the government would support the introduction of the law for patients in hospitals.

Matha’s mother says:

… More important is something that’s obvious but doesn’t get said enough: our trust in doctors should have limits. Medicine is like any other job: there are many talented workers in the NHS, but also those who are less dedicated and less able.

Think of the old medics’ joke: “What do you call the guy who graduated last in his medical school class?” “Doctor.”

There are plenty of clinicians prone to arrogance and complacency. Some doctors are “heroes”, but we should stop thinking of them all as such.

How these issues showed up in The Post Office Scandal

The dismissal of tacit or non-expert knowledge

It is hard to fathom how experts and investigators and lawyers from the Post Office and Fujitsu dismissed the tacit knowledge of hundreds of subpostmasters. Why did they not listen to the protestations of innocence or respond to a growing pattern of prosecutions? Instead – proceeding with false prosecutions.

It is hard to imagine that this was not done deliberately.

The evidence and findings of the Public Inquiry over the coming months will be critical to understanding what happened. The narratives and biases used to justify this failure to listen will be important to help us make systemic changes.

Misplaced Trust

Regarding misplaced trust, the obvious issue was that the Horizon accounting system was trusted over the subpostmasters. This creates challenging questions for the digital and AI age. Where we are already seeing algorithms taking on management functions such as the hiring and firing of employees.

Additionally, the reputation of the Post Office as a ‘trustworthy’ institution led to many subpostmasters being viewed as criminals. Many were rejected by their communities who placed trust in the Post Office over the word of their local subpostmasters. The stress and impact this had on peoples lives cannot be underestimated.

Seema Misra was pregnant with her second child when she was convicted of theft and sent to jail in 2010. Seema became a post office operator in Surrey in 2005. Three years later she was suspended due to an accounting discrepency of £74,000. She attempted to balance her books by borrowing money and transferring takings. But she could not repay what was supposedly owned and was eventually jailed. The press described her as the ‘pregnant thief’ and her husband was beaten up by locals. Seema’s conviction was overturned in 2021.

But there is a more nuanced expression of this misplaced trust. That smacks of gaslighting.

Where – in some cases – the subpostmasters thought they must be in the wrong, trusting the Post Office over themselves.

For example, Jo Hamilton bought a village shop in 2001 and created a community hub where people dropped in for tea and her baking. From 2003 the Horizon system began to show shortfalls on her accounts – she assumed it was her fault saying

“I always thought what it said must be right because it’s a computer and I’m a dumb-dumb… I never gave it a minute’s thought that the Post Office would do that to me. And then you ring up the helpdesk and they say: ‘Well, you are the only one that’s had problems with it.’ ”

She was eventually sacked by the Post Office and charged with stealing £36,000. In 2008, she agreed to plead guilty to a lesser charge of false accounting to avoid prison. She had to pay back the supposedly missing £36,000. And again remortgaged her house. The village (who did not lose trust in her) chipped in £6,000.

Her prosecution was ruled unfair and an affront to justice in 2021. During legal proceedings it emerged that the Post Office’s own investigator had found no evidence of theft.

How these issues showed up at Grenfell

At Grenfell, we again see these issues playing out with devestating consequences.

The dismissal of tacit or non-expert knowledge

Regarding non-expert views being dismissed, residents repeatedly raised concerns about safety before the Grenfell Tower Fire and these were dismissed. In a now (in)famous blog, written just 7 months before the fire, resident Ed Daffarn and Francis O’Connor said.

Kensington & Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCMTO) Playing with Fire

20 November 2016

It is a truly terrifying thought but the Grenfell Action Group firmly believe that only a catastrophic event will expose the ineptitude and incompetence of our landlord, the KCTMO, and bring an end to the dangerous living conditions and neglect of health and safety legislation that they inflict upon their tenants and leaseholders…

Unfortunately, the Grenfell Action Group have reached the conclusion that only an incident that results in serious loss of life of KCTMO residents will allow the external scrutiny to occur that will shine a light on the practices that characterise the malign governance of this non-functioning organisation…

It is our conviction that a serious fire in a tower block or similar high density residential property is the most likely reason that those who wield power at the KCTMO will be found out and brought to justice! …

We have blogged many times on the subject of fire safety at Grenfell Tower and we believe that these investigations will form a crucial part of a damning catalogue of evidence showing the poor safety record of the KCTMO should a fire affect any other of their properties and cause the loss of life that we are predicting.

During the Grenfell Inquiry we have heard evidence that those responsible for the safety of residents didn’t look at the blog . It had effectively been ‘banned’ and Ed was seen as a trouble maker. His views not considered seriously. I write about this in more detail here.

Prior to the fire, residents flagged issues about a broken self-closing door mechanism and the failure to consult them on the selection of cladding and windows. The windows and the cladding were critical to the rapid spread of the fire. The failure of doors to close on the night contributed to rapidly deteriorating conditions inhibiting rescue and escape. These were opportunities to learn from the tacit knowledge of residents that were dismissed.

I would highly recommend listening to this interview with Grenfell survivor Ed Daffarn and LBC’s James O’Brien. And, the Channel 4 Documentary ‘Grenfell the Untold Story’ shows in detail how the views of residents were repeatedly dismissed. Be warned, you will be outraged.

Misplaced Trust

Regarding misplaced trust, residents were told by the London Fire Brigades (LFB) Control Room Operators to stay put. That someone would come and rescue them when this was not the case. Some residents placed their trust in the LFB. Listening to their advice to stay, over the pleas from friends and family to leave.

This advice to stay put was made despite recommendations from the 2009 Lakanal House Fire. Six people died, and the Inquest recommended that the LFB not give people false hope that someone was coming to rescue them when it was not known if this was the case. I write more about this here.

We cannot separate the issues of misplaced trust and the failure to listen to other ways of knowing from power. Whose voices count, who we trust and who we listen to are intricately woven into power narratives.

We are unlikely to make progress until those in positions of power understand the dark side of expertise and lead with humility and curiosity. With a committment to rebalance power and listen to and actively learn from non-expert or tacit knowledge.

This will require understanding and exploring the biases and narratives that justify our willingness to dismiss certain voices and ways of ‘knowing’.

Unfairly borne consequences

A systemic issue

There is understandably disdane and outrage regarding the lack of accountability in the Post Office Scandal. But this issue of unfairly borne consequ ences is systemic.

The reality is that consequences are unfairly borne. Both in terms of a failure to hold people to account but also in terms of redress. Such as with the delayed compensation payments in the Post Office Scandal. Mr Bates has said that

The big hold up for the compensation is to speed the bureaucracy up which is holding up the payments to all these people. They really must light a fire under their officials to get this sorted,” Mr Bates said, and added that about 60 to 70 claimants had died before getting justice.

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-67899189

And in the case of the Building Safety Crisis following Grenfell. Where innocent leaseholders are bearing the brunt of unsafe buildings while the government fails to deliver fair and effective mechansims for remediating historical safety issues. A 2021 report into the impacts said:

For many leaseholders, the building safety crisis challenged their self-perception, foundational components of their identity, and their view of wider society and their place and value within it.

Many participants were frustrated with policy developments and felt that it was now necessary for Government to lead a process to identify, assess, and remediate buildings systematically, based on a prioritisation of risks. This would require significant Government funding, but there was considerable desire to see relevant organisations held accountable.

https://housingevidence.ac.uk/publications/living-through-the-building-safety-crisis/

There are two key issues that contribute to this failure to hold people to account or adequately redress, remediate and compensate:

- Our obsession with blame and blame avoidance which is intrinsically linked with power and makes learning and change almost impossible.

- The ineffectiveness and complexity of government scrutiny and delivery mechanims which inhibits fair and fast redress.

After touching further on consequences in both the Post Office Scandal and Grenfell, I’ll explore each of these systemic issues.

The Post Office Scandal and consequences

In the Post Office Scandal, nobody has been held to account either from Fujitsu or the Post Office. There is a criminal investigation and a Public Inquiry underway and this may change. Since the airing of the ITV Drama there have been calls for one of it’s former heads – Paula Vennels – to have her OBE (given for services to the Post Office) removed. Within a couple of days, a public petition to this effect has ammassed nearly 100,000 signatures. On the 9th of January responding to this pressure she said she would return her OBE.

The following video with James Harley at Free’s LLP who works on behalf of many of the postmasters considers how prosecutions and other consequences could play out regarding the Post Office Scandal.

This includes considering issues with procurement – considering that Fujitsu have been awarded £142 million in government contracts since the statutory Post Office Inquiry was announced.

Grenfell and consequences

Likewise with Grenfell (and Hillsborough, and the Infected Blood Scandal and Covid – the list is endless) no-one has been held accountable. The Grenfell Public Inquiry is due to publish it’s final report this year and criminal prosecutions may follow.

In the case of Grenfell these consequences are borne in the suffering of those directly impacted. But also in the resultant building safety crisis where thousands of lives have been impacted and devestated.

As the scale of unsafe buildings has become clear, issues of who pays for and how to prioritise and manage remediation has led to what is called the building safety crisis or cladding scandal. Thousands of people are living in unsafe homes, that they cannot sell or remortgage and in some cases cannot insure. Whilst the government has implemented complex arrangements to limit leaseholder liability and promote remediation, these processes are not always effective and many leaseholders have ended up paying hundreds of thousands to remediate unsafe buildings.

The Sunday Times estimates that 8% of people living in England have been caught up in the fallout of the building safety crisis.

Let us look at the two issues that contribute to our failure to either hold people to account or effectively and efficiently redress or compensate those impacted.

Our obsession with blame and blame avoidance

The public (and media’s) obsession with finding individuals to blame often means we don’t consider the deeper systemic issues. It is not that individuals should not be prosecuted or held to account (for e.g., losing jobs, positions, stature) – they should. It is that individual (or organisational) accountability does not equate to change or learning.

Simply removing people from a corrupt or broken system doesn’t change the system itself. The conditions that surrounded the immoral and unethical behaviours don’t change, leading to the likelihood that the underlying issues will persist, and behaviours will be repeated in the future.

Additionally, the obsession by politicians with avoiding blame can drive a lack of disclosure. And is an incentive to sweep things under the carpet and hope no-one finds out ‘on my watch‘. This can drive a failure to admit to issues in a timely manner. I explore this in detail in an episode of Catastrophe the podcast.

Without a significant shift away from blame and blame avoidance and toward creating conditions that allow for learning and change , we will continue to be outraged and surprised as the failures that lead to these disasters and miscarriages of justice come to light.

Interestingly, the government recently rejected the Hillsborough Law that would have made a duty of candour legally enforcable. The law was proposed by victims and families of the Hillsborough Stadium disaster that killed 87 people in 1989. The families have campaigned for truth and justice for 25 years, after police lied about and blamed the victims for the stadium crush.

The government also rejected a proposal by the families, to extend public funding for bereaved families at inquests. This lack of equity in access to legal counsel is a key imbalance of power.

It played out in the Post Office Scandal (not in relationship to Inquests) as the might and weight of the post office was brought to bear on innocent subpostmasters.

For example, the Post Office took Lee Castleton, a subpostmaster in Bridlington, to court over an unexplained shortfall of £35,000. Castleton, was one of the first seven victims interviewed by Computer Weekly. He refused to pay the money, citing computer problems as the cause of the shortfall. The Post Office spent over £300,000 crushing Castleton in court. Castleton defended himself and lost. It bankrupted him and devastated his and his family’s life.

So, cries for finding who to blame and ensuring individuals are held to account are understandable and important. But they can stop us from exploring, understanding and addressing the deeper systemic issues at play.

The ineffectiveness and complexity of government scrutiny and delivery mechanims

The final systemic issue I want to explore is the ineffectiveness and complexity of government scrutiny and delivery mechanisms. Why can the government not ensure rapid compensation for victims of the Post Office Scandal? Why has the government not effectively risk assessed, priorited and paid for the remediation of unsafe buildings in the wake of Grenfell. Why have we not successfully compensated victims of the Infected Blood Scandal or the Windrush Generation.

There are three contributing factors: the sheer scale of government, issues with accountability, and problematic reactive scrutiny mechanisms.

The sheer scale of government

The sheer scale of government makes it difficult to effectively deliver on things like compensation (in the Post Office Scandal) or remediation of unsafe buildings in a post-Grenfell context. This is particularly true when multiple deparments and agencies are involved.

- In addition to approximately 20 Cabinet Ministers (the most senior members of government), around 100 additional Ministers are selected from Parliament. They are responsible for the decisions and actions of their departments.

- Various bodies are then accountable for putting government policy into practice. There are

- 24 ministerial departments (such as the Ministry for Housing and Local Government).

- 20 non ministerial departments that usually have a regulatory or inspection function (such as the National Fraud Office).

- And over 300 other agencies and public bodies. Whose role is usually to provide government service rather than decide policy. For example the Health and Safety Executive which is sponsored by the Department for Work and Pensions.

- The Civil Service does the practical work of government. In September 2019 there were 419 000 Civil Servants.

- In England more than one million people work for local governments. Taking varying forms they are responsible for a range of services within a defined area. Local governements are accountability for (among other things) planning, fire and public safety, social care and housing.

- Devolved Governments in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are responsible for many domestic policy issues . Such as health, transport and education, and they have law-making powers in those areas.

The sheer scale of government makes effectively delivering change difficult. This is made worse by issues with accountability.

Issues with accountability

A 2018 Institute for Government report, ‘Accountability in Modern Government’ says: “accountability is about a relationship between those responsible for something, and those who have a role in passing judgement on how well that responsibility has been discharged.”

However, the report highlights issues with accountability in UK’s Government. These include:

- lack of clarity about who is responsible;

- no consequences for good and bad performance and

- lack of transparency and information.

Fundamental gaps in accountability have led to relationships between officials and ministers that “promote a tradition of secrecy, which results in a lack of clarity about the responsibilities of senior officials and ministers.”

‘Accountability in Modern Government’ The Institute for Government

In addition, there is a failure to ensure that accountability has kept pace with increasing complexity of government at all levels including local and devolved governments. Services are delivered through complex networks of departments, public bodies, private and voluntary sector providers with inconsistent oversight, inspection, regulation and scrutiny.

And the high turnover of both ministers and the civil service adds to failures of accountabilities. As new incumbents bring different priorities and visions and struggle to maintain knowledge and expertise. As of January 2020, three quarters of Ministers had only been in post for six months. Of relevance to Grenfell, the Ministry of Housing and Local Government lost almost a quarter of its staff in 2017/2018, a third of Cabinet Office staff change each year.

Possibly exacerbated by the political turmoil surrounding Brexit, the trend for Ministers to remain in positions for shorter periods is troubling. From an accountability perspective, as former chancellor Kenneth Clarke told the Institute for Government:

“After six months… you have got an agenda. You know exactly what you are going to do. The next stage, after two years, you are really on top of it… But you realise that the decisions you took after six months were wrong and you have changed your mind. After two years, you are sitting in control now, behind your desk, where you are really going to do this, this, and this. And then the phone rings and the prime minister is having a reshuffle and you move on to the next department and you are back at the beginning, there you are, panicking again.”

Chancellor Ken Clarke, in ‘Accountability in Modern Government’ The Institute for Government

Issues with Scrutiny Mechanisms

So we have a massive governement system that has weakness in accountability which is problematic. Add to this, issues with the scrutiny mechanisms in place to investigate disasters and miscarriages of justice and we have a lethal combination.

Rather than reliable and count-on-able sources of justice and the truth, the mechanisms we have to investigate and respond to these miscarriages of justice are flawed.

The table below outlines the types of investigations available.

| Statutory Inquiry | Non-Statutory Inquiry | Inquest | Independent Panel | |

| Established | By minister… when events cause particular public concern | By a coroner whenever a death occurs under specific circumstances | By a minister | |

| Examples | Grenfell | Morecambe Bay Hospital | Lakanal House | Hillsborough |

| Terms of Reference | Set by minister | No specific TORs | Set by Minister | |

| Public or Private | Public to greatest extent possible | Presumed public but may sit partially or wholly in private | Public with option that some evidence can be heard in private | Public |

| Led | Chair with option of panel | Coroner | Chair led panel (usually 4 – 12) | |

| Duration | 1 – 6 years | Less than a year | 1 to 3 years | |

| Can compel testimony & production of documents under criminal sanction | Y | N | Y | N |

| Can take testimony under oath | Y | N | Y | N |

| Public access to documents | Duty to ensure this | No duty to ensure this | Duty to disclose relevant document | Usually disclosed |

| Maxwellisation (core participants see and respond to findings prior to publication) | Must take place | Generally expected | No Maxwellisation process | |

| Core Participants status available | Available for individuals, organisations and institutions with a specific interest, provides special rights | Not available | ||

| Recommendations | Usually required by Terms of reference | Required by statute in Prevention of Future Deaths Report | Sometimes required | |

Adapted from Emma Norris and Marcus Shepheard. 2017. ‘How public enquiries can lead to change’. Report, Institute for Government,

Key issues with the available approaches are:

- Apart from an Inquest, it is up to the discretion of Ministers to call for these (or not); appoint chairs and panels and set terms of reference. This calls into question their independence.

- These public investigations are complex, costly and rarely satisfy everybody. Concurrent criminal investigations and court proceedings complicate matters and can extend timelines for corrective actions and prosecutions. A 2017 Institute for Government report estimated that £638.9m had been spent on 68 public inquiries alone since 1990. By June 2023 the Grenfell Inquiry had cost £170 million.

- Notably, there is no process for ensuring that recommendations are either implemented or effective. Ministers are free to either accept or reject recommendations. Once accepted there is no process for following up on progress. According to the Institute for Government, of the 68 inquiries that have taken place since 1990, only six have received a full follow-up by a select committee to ensure that government has acted.

A 2020 report by JUSTICE, an all-party law reform and human rights organisation raised various issues with the current system, including:

- The political nature of the decision to call for a public inquiry

- The discrepancy between the rights afforded to victims in the judicial systems and the lesser rights granted to bereaved and survivors in Inquests and Inquiries. This on top of a lack of co-ordination between agencies leads to those most impacted needing to share their traumatic experiences on numerous occasions to different bodies.

- Institutional defensiveness which can impede the effectiveness of Inquiries and Inquests and damages public trust. The report recommends establishing a statutory duty of candour requiring participants to lay their ‘cards on the table’ thus directing the Inquiry to key issues early in the process, reducing time and costs.

Regarding the implementation of recommendations, the report calls for an external oversight saying:

Quite apart from those instances where Government has indicated that recommendations will be implemented, there is no routine procedure for Ministers to explain why they have rejected inquiry recommendations. After initial investigations, several rounds of written and oral evidence, analysis and a final report, there is little to prevent inquiry recommendations vanishing into the ether where the political will to implement is lacking.

When Things Go Wrong, 2020, JUSTICE

In essence, our reactive mechanism for investigating and preventing catastrophic events are set up at the whim of the sitting government; are costly and lengthy; are burdensome on the bereaved and survivors and there is no mechanism for ensuring their recommendations are either implemented or effective.

This combined with the scale of government, its complex and ineffective delivery mechanisms and weaknesses in accountability mean we should not be surprised that our responses to disasters and miscarriages of justice routinely fall short.

Summary and Conclusions

My heart breaks for the victims of the Post Office Scandal, their families and communities. I am thrilled this is finally getting the publicity and resultant public pressure for change that is needed.

Two key systemic issues that I’ve explored in this blog are:

- The role of knowledge and power in silencing voices. And specifically how misplaced trust and the dismissal of non-expert or tacit knowledge can have devestating consequences. Power and whose voices and knowledge count are deeply entwined with this issue. As the world changes and we are faced with complex challenges (WICKED / VUCA /BANI call it what you will), the role and reliability of traditional deep domain expertise is changing. All of our voices are needed and we need politicians that lead with humilty and curiosity. This is sadly lacking and with the emergence of AI and it’s impact in this space, I fear deeply for the future.

- How and why the consequences of these events are so unfairly borne. There are systemic issues with effectively holding individuals and organisations to account after disasters and miscarriages of justice. Additionally the consequences are unfarily borne by the victims not the perpetrators. The systemic issues here include our obsession with blame and blame avoidance and the ineffectivenss of governement scrutiny and delivery mechanisms. This is due to the sheer scale of government, weaknesses in accountability and issues with our post disaster scrutiny mehcanisms such as Inquiries.

The issues the Post Office Scandal highlights are systemic and if we are serious about justice and learning and change we need to tackle these gnarly complex problems.

This will require moving beyond sensationalist media coverage - that will soon move on – and relentlessly demand change for all victims of disasters and miscarriages of justice.

That is down to all of us.

References

https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-56718036

https://www.postofficehorizoninquiry.org.uk/about-inquiry

https://www.gov.uk/government/how-government-works

www.sshls.port.ac.uk/hub/public-policy/structures/british-constitution/

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/whitehall-monitor-2020/civil-service

https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/publication/report/how-public-inquiries-can-lead-change

https://www.local.gov.uk/about/what-local-government

https://civilservant.org.uk/the_westminster_model-accountability.html

Institute for Governement (2017) Emma Norris and Marcus Shepheard. 2017. ‘How public enquiries can lead to change’. Report, Institute for Government, https://www.regulation.org.uk/library/2017-NAO-A-Short-Guide-to-Regulation.pdf

JUSTICE. 2020. ‘When Things Go Wrong: The response of the justice system’. (https://justice.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/flipbook/34/book.html).

Nick Wallis’s website and book are invaluable resources.

About Me

I lived in Grenfell from 2011 to 2014. As I watched the fire on the 14th June 2017 I promised to do what I could to make sure we learned. At the time of the fire, I worked as a consultant in high hazard industries. My job was to partner organisations to develop the leadership capabilities and cultures to prevent catastrophic events. My interest is both professional and personal.

I campaign, speak and write to bring about change. In 2021 I published ‘Catastrophe and Systemic Change: Learning from the Grenfell Tower Fire and Other Disasters.’ The book is part of the London Publishing Parnterships Perspectives Series that is edited by Diane Coyle.

In 2022 I joined Arup University as Transformation Director with a committment to be part of post-Grenfell change, rather than commenting from the outside.

Leave a reply to Anonymous Cancel reply